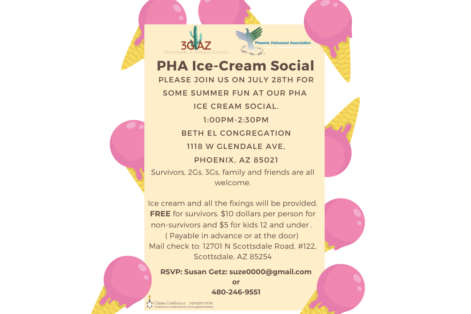

Sheryl Bronkesh shudders whenever she is reminded that with each passing year, the local Holocaust survivors she works with, and has grown to love, get older and increasingly frail. Bronkesh, president of the Phoenix Holocaust Association (PHA), originally joined the organization for the sake of her parents, both of whom survived the Holocaust and are now deceased.

About 245,000 Holocaust survivors remain alive today, according to a January demographic report by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, an organization that has worked to ensure survivors are compensated for their suffering. The median age of survivors today is 86.

The Claims Conference negotiates aid for survivors with Germany annually, shares the basic information it collects publicly and offered a similar number of estimated survivors last year. But this latest report is the first to break down the population of Jewish survivors by country of birth and current country of residence, their age, gender, compensation and services received.

It identified survivors in more than 90 countries: 49% reside in Israel, 18% in North America, another 18% in Western Europe and 12% in the former Soviet Union.

The youngest are on the cusp of 80 — the Holocaust ended in 1945 — and, in a reflection of geriatric gender disparities, 61% are women.

Those percentages mirror Arizona’s population of survivors, Bronkesh told Jewish News.

There are just over 60 survivors in Greater Phoenix, and Tucson has about 20. Two survivors, both men, passed away in January. The number increased by one recently, when a survivor moved to Phoenix from another state.

The Claims Conference was founded in 1951, and over the decades has negotiated various compensation programs with the German government for survivors around the world, mainly distributed through local service agencies. Last year, the Claims Conference negotiated $1.4 billion in compensation, a record high that the group said was needed to cover the higher costs incurred by an aging population. Survivors receive an array of support, from direct payments and pensions to home care, food, medicine, transportation and social programs.

In Greater Phoenix, any survivor getting reparations is contacted by Jewish Family & Children’s Services (JFCS), which then connects them to PHA. In fact, JFCS introduced Bronkesh and her parents to the organization she now leads.

The new demographic report is based in part on information about Jews served by such programs. The data were combined with published reports on the number of recipients receiving compensation administered by Israel, Germany and Austria.

“We say we have about 80 survivors in the state but there could be more survivors who don’t want to make their status known,” Bronkesh said. She knows of no others in the state outside of the Phoenix and Tucson metro areas. Though some survivors may choose not to be identified, the Claims Conference reported that there are still occasional applications for compensation.

The Claims Conference also funds Holocaust education efforts, and this new report starkly demonstrates the loss of living witnesses to the 20th century’s most profound atrocity. Even with a few new cases added, the overall survivor population is dwindling — an expected trend that has worried schools and synagogues that have depended on survivors to teach about the Holocaust.

It’s a reality that Bronkesh understands all too well. As a younger woman, busy with other things, she considered PHA to be her parents’ organization, and though she honored Yom HaShoah alongside them every year, she didn’t do much else. “But when they needed this next generation to step up, I stepped up,” she said.

Now, as the number of remaining survivors dwindles further, she and her fellow 2Gs and 3Gs (second- and third-generation survivors), are doing more of the heavy lifting, especially when it comes to educating younger generations about the Holocaust.

“We’re descendants and we want to stay relevant even when there are no living survivors,” Bronkesh said. “We speak to schools and the general public; it’s one of PHA’s most important missions.”

The survivors who are still able to speak in public often take a 2G along to help. Bronkesh provided this kind of help for her mother before she passed away, prompting her whenever she forgot parts of her story.

She also has an audio recording of her father talking about what it was like living underground in the woods as a partisan during the war. While he had a strong accent and didn’t speak English very well, she’s still able to use certain clips — “we lived like rats and mice underground, one on top of each other” — to great effect. She donated the recording to Yad Vashem in Jerusalem.

“We are working with our 2Gs who want to tell their parents’ stories and help them find ways to make their presentations stronger. We also have the grandchildren, 3Gs, who do this very successfully,” Bronkesh said.

PHA also helps survivors present on Zoom but said that so many students “are mesmerized by the survivors, don’t want them to stop talking and want to take a selfie with them,” knowing they’ll be the last generation to meet a survivor in person.

For their part, the survivors, while increasingly diminished physically, are committed to continuing their witness as long as they can. “Some don’t feel they’ve done enough,” Bronkesh said.

At 96, Prescott survivor Esther Basch is still hard at work finishing “The Honey Girl,” a documentary about her experience in the Holocaust, with the help of her daughter. Bronkesh was recently contacted by a professor at Colorado State University in Fort Collins, who was interested in bringing a survivor to Colorado because there are no survivors in Fort Collins nor even in nearby Denver.

Bronkesh wanted to help but said the university would also need to fly a caregiver because no survivors are capable of going alone. She called Basch, but it turned out that she was already booked for a speaking gig in Montana. Basch’s daughter said adding Colorado to the itinerary would be too much, but her mother called Bronkesh back and said, “I can do it. As long as I’m alive, I want to do it. Let me work on my daughter.”

“She knows she’s fragile but she wants to finish her film,” Bronkesh said. “Then she went and arranged another event in Denver!”

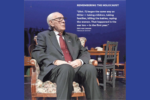

A few years ago, local survivor Oskar Knoblauch sat immobilized in a chair in the same clothes for six or seven hours every day for a total of five days, and was asked a litany of questions over and over to create a 3D life-size holographic-like video, technology that allows visitors to have a virtual conversation with him as he shares his story and answers a range of questions.

This exhibit was unveiled at the Arizona Jewish Historical Society (AZJHS) in 2022. Its creators initially thought about waiting until after the COVID-19 pandemic was completely over to film him, but Bronkesh told them, “You can’t risk waiting,” and Knoblauch agreed.

“It’s simple: Aging is something we cannot stop and we’re not going to hang around much longer,” he told Jewish News. He has been educating people for more than a decade but now says, “I started much too late.”

He said his holographic image, and others like it, will be useful for education, but “nothing can replace the real person, ever, but this is close.”

The 99-year-old Knoblauch was delighted that Arizona passed mandatory Holocaust education in 2021, but still worries that it isn’t enough. “Any genocide, any abuse, including gruesome parts of American history, has to be taught because if students don’t learn, they will listen to the wrong sources and believe them because that’s all they’ll know,” he said.

“I’m always the oldest person in the room, but I was there and saw so many things that most won’t see and we can’t pass that on when we’re gone. It should have been passed on years ago,” he said.

Not every survivor in Arizona experienced a concentration camp or even has many memories to share.

Julie Gutfruend is from Vienna, Austria. In 1938, she was seven years old and hardly aware of what was going on around her. She remembers bits and pieces from Kristallnacht or the Night of Broken Glass.

“My mother and I were at home; a Nazi truck went by our house and the people were shouting, ‘Jews Get Out!’ They knocked on our door and we hid in the closet. I thought they were looking for criminals or something. We hid in the closet and they pounded on doors and we didn’t come out,” she told Jewish News.

Gutfruend moved to Phoenix in 2009 and joined PHA mainly to socialize. She didn’t talk much about her past though AZJHS and the Spielberg Foundation interviewed her.

“I didn’t say I was a survivor for a long time because my family managed to leave before things were really bad. It began slowly and nobody knew what it would turn out to be,” she said

Kathy Gross grew up in Budapest, Hungary and was six when the Nazis invaded. Luckily, she was hidden from the Nazis, along with a few other children. Most of her family was killed in the Holocaust but Gross’ mother, who survived both by faking her death and later by getting false papers that enabled her to hide in Budapest, recovered her little daughter after the war. Gross never learned how her mother was able to find her.

They stayed in Hungary until 1956.

“I know I suffered from deprivation and discrimination but I couldn’t sense the emotional impact on the grownups,” she told Jewish News.

After the war, Hungary was taken over by a Soviet-allied government and became part of the Eastern Bloc and antisemitic sentiment remained high.

“In school, you had to tell your religion and your father’s profession and financial situation, and that caused me to be an outcast. My father died in the Holocaust but before the war, he owned a factory and my mother rebuilt it, so that meant I was a ‘Jewish capitalist’ and they wouldn’t let me go to college,” she said.

Her only choice was to go to a technical school where she learned to make shoes. She worked in a shoe factory before leaving for England in 1956, and still has her diploma.

“I felt the trauma of the bombing during the war, but I couldn’t sense the fright of the adults. I am still trying to figure out why I never missed my parents; I can’t recollect any of those feelings. Perhaps it’s a result of trauma or my age, I don’t know. I never asked. I hardly remember my father or my sister, who died of polio in 1945,” she said.

She still works in her travel agency and said that running a business and interpreting for the court system didn’t leave her much time to spare for speaking publicly about her past. Now, she regrets not doing it.

“The situation in Israel and rising antisemitism really pushed me to do something. I felt maybe I owe something to give back,” she said.

She doesn’t feel confident speaking in front of classrooms, but she gave AZJHS an interview and thinks its work in Holocaust education “is just amazing and extremely impressive.”

Through PHA and its Café Europa program, she has interacted with other survivors and even met other Hungarians. “I’m interested in their stories. Now that I’m in PHA, I’m getting involved,” she said. She represented survivors at the State House’s opening day session in January and testified on behalf of Holocaust education earlier this month.

“I really can’t describe the horrors of the camp, but I may volunteer to go to a school that’s not far from me,” she said. “I want to do what I can.” JN

This article incorporated reporting from the Jewish Telegraphic Agency

This post has been contributed by a third party. The opinions, facts and any media content are presented solely by the author, and JewishPhoenix assumes no responsibility for them. MORE